|

New research is unlocking the amazing potential

of high-temperature superconductors.

by Patrick L. Barry

Few technologies ever enjoy the sort

of rock-star celebrity that superconductors received in the late

1980s.

Headlines the world over trumpeted the discovery of "high temperature"

superconductors (abbreviated HTS), and the media and scientists

alike gushed over the marvels that we could soon expect from this

promising young technology. Levitating 300-mph trains, ultra-fast

computers, and cheaper, cleaner electricity were to be just the

beginning of its long and illustrious career.

Today we might ask, like a Hollywood

gossip columnist: what ever happened to the "high-temp" hype?

"It was the hottest potato of its

time, but it all fizzled out," says Louis Castellani, president

of the Houston-based HTS company Metal Oxide Technologies, Inc.

(MetOx).

The problem was learning to make wire out of it. These superconductors

are made of ceramics - the same kind of material in coffee mugs.

Ceramics are hard and brittle. Finding an industrial way to make

long, flexible wires out of them was going to be difficult.

Indeed, the first attempts were disappointing.

So-called "first generation" HTS wire was relatively expensive:

5 to 10 times the cost of copper wire. Furthermore, the amount of

current it could carry often fell far short of its potential: only

2 or 3 times that of copper, versus a potential of more than 100

times.

Image courtesy MetOx

"Second

generation" HTS wire can carry the same amount of current

as copper wire hundreds of times as thick.

|

But now, thanks to years of research

involving experiments flown on the space shuttle, this is about

to change.

The NASA-funded Texas Centre for Superconductivity

and Advanced Materials (TcSAM) at the University of Houston is teaming

with MetOx to produce the "smash hit" that scientists have been

seeking since the '80s: a "second generation" HTS wire that realizes

the full 100-fold improvement in current capacity over copper yet

costs about the same as copper to produce.

Once-famous superconductors may be

about to step back into the limelight.

The audience awaits

The special "talent" of superconductors

is that they have zero resistance to electric current. Absolutely

none. In theory, a loop of HTS wire could carry a circling current

forever without even needing a power source to keep it going.

In normal conductors, such as copper

wire, the atoms of the wire impede the free flow of electrons, sapping

the current's energy and squandering it as heat.

Today, about 6 to 7% of the electricity

generated in the United States gets lost along the way to consumers,

partly due to the resistance of transmission lines, according to

U.S. Energy Information Agency documents.

Replacing these lines with superconducting wire would boost utilities'

efficiencies, and would go a long way toward curbing the nation's

greenhouse gas emissions.

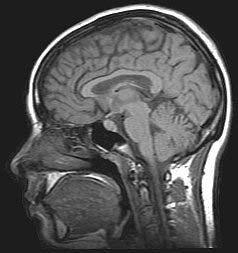

MRI scans,

a powerful tool for medical diagnosis, use superconducting

electromagnets to generate detailed images of body tissues.

Most of today's MRI machines require expensive liquid helium

to cool their low-temperature superconducting wire.

|

The fledgling "maglev" train industry

would also welcome the availability of higher-quality, cheaper HTS

wire. Economic realities stalled the initial adoption of maglev

transit systems, but maglev development is still strong in Japan,

China, Germany, and the United States.

NASA is looking at how superconductors

could be used for space. For example, the gyros that keep satellites

oriented could use frictionless bearings made from superconducting

magnets, improving the satellites' precision. Also, the electric

motors aboard spacecraft could be a mere 1/4 to 1/6 the size of

non-superconducting motors, saving precious volume and weight in

the spacecraft's design.

Should we ever establish a base on the moon, superconductors would

be a natural choice for ultra-efficient power generation and transmission,

since ambient temperatures plummet to 100 K (-173 C, -280 F) during

the long lunar night - just the right temperature for HTS to operate.

And during the months-long journey to Mars, a "table top" MRI machine

made possible by HTS wire would be a powerful diagnosis tool to

help ensure the health of the crew.

Worldwide, the current market for HTS

wire is estimated to be US$30 billion, according to Castellani,

and it is expected to grow rapidly.

A backstage pass

The University of Houston has licensed

this new wire-making technology to MetOx, a company founded in 1997.

MetOx plans to begin full-scale production of this high-quality

HTS wire in 2003, Castellani says.

Not surprisingly, the primary scientist

for the NASA group at TcSAM, Dr. Alex Ignatiev, can't reveal exactly

how they make their HTS wire. The technologies springing from these

NASA/industry research partnerships must be patented to achieve

NASA's goal of using space to benefit American businesses, Ignatiev

says.

Image courtesy NASA

The Wake

Shield Facility being held out in space by the shuttle's

robot arm.

|

He will, however, share the dinner-napkin

sketch.

Basically, the wire is made by growing

a thin film of the superconductor only a few microns thick (thousandths

of a millimetre) onto a flexible foundation. This well-known production

method was improved upon in part through "Wake

Shield" experiments flown on the space shuttle to learn about

growing thin films in the hard vacuum of space.

"We learned how to grow higher-quality

oxide thin films from the shuttle experiments, and used that in

the lab to improve the quality of our superconducting films," Ignatiev

says.

In the years to come, that quality

will translate into improvements in dozens of industries from power

generation to medical care. Keep an eye on this one: the glamorous

career of superconductors has only just begun.

|