From the dawn of time, people have suspected powerful forces lurking

deep in the oceans ‚ from the Greeks' fearsome sea-god Neptune

to John Wyndham's submarine aliens in his 1950s novel The Kraken

Wakes. But science is once again going one better than science

fiction. Researchers are discovering that hidden 'rivers' run through

the oceans, and these powerful currents hold the destiny of our

planet's climate.

The beneficial aspects of ocean currents have long been known.

For countries on the east side of the Atlantic, winters are a balmy

holiday compared with the same latitudes on the west: the frigid

coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador. It's a reminder that "weather"

is not just a matter of the Sun's heat affecting the Earth's atmosphere.

The world's interconnected oceans can store up solar heat in one

part of the globe in one season, and invisible rivers in the ocean

can transport the warmth thousands of kilometres to another part

of the globe and deliver it in another season.

In the case of the North Atlantic, heat is carried northward and

eastward by the Gulf Stream. This current warms the coast evenly

through the year, in winter as well as summer. Averaged over a year,

the Gulf Stream provides Western Europe with a third as much warmth

as the Sun does.

This ocean warmth is so important to Europe that climatologists

are seriously concerned about the stability of the Gulf Stream.

If it switched off, Europe would be plunged into a mini-Ice Age.

And current studies suggest that the unseen river in the North Atlantic

is dangerously fickle.

The focus of today's worries is the problem of global warming

- the way that human activities are changing the climate, as the

world gets warmer through the build-up of so-called greenhouse gases,

such as carbon dioxide. Climatologists think that global warming

may put the brakes on the Gulf Stream. While the rest of the world

comes to swelter in greenhouse conditions, Europe would freeze!

This concern is based on a new understanding of how the great

ocean currents are all interconnected. The Gulf Stream is part of

a giant pattern of moving water that stretches right around the

globe.

The Ocean Conveyor Belt

The warm water that is so important to Europe actually comes from

the other side of the world, in the Pacific Ocean. This tepid stream,

flowing unseen through the oceans, is the longest river in the world.

It flows along the surface, both because it is warm (and warm water,

like warm air, rises) and because it is less salty ‚ and so

less dense - than the deeper water. The warm waters travel westward

from the central Pacific, past the north coast of Australia and

round the southern tip of Africa before moving up into the Atlantic.

|

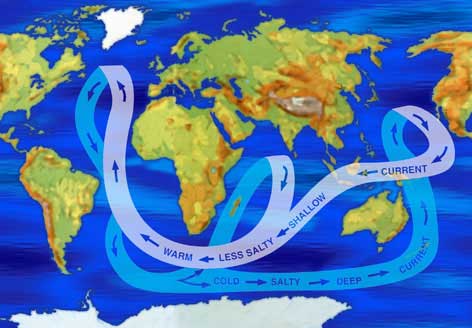

The present

state of the 'ocean conveyor belt' that transfers warm, less

salty water from the Pacific to the Atlantic as a shallow current,

and returns cold, more salty water from the Atlantic to the

Pacific as a deep current flowing further south. This flow is

threatened by melting ice in the Arctic, and disruptions off

the Antarctic coast. |

|

|

photo

- Pioneer Online Ltd.

|

|

This great ocean river becomes the Gulf Stream by the time it

heads up through the North Atlantic. But as the current surges past

Europe, its nature begins to change. It cools down significantly

as it gives up its precious heat to the European seaboard. And,

all along its long journey, the warmth of this invisible river has

encouraged water to evaporate from its surface layer, so it becomes

increasingly salty. Around the latitude of Iceland, the moving stream

becomes so dense that it sinks into the depths.

This stream now becomes a cold river, flowing back along the ocean

floor. Rounding the south of Africa and Australia, it returns to

the Pacific, where it is pushed to the surface and warms to complete

the cycle. The whole effect is like a conveyor belt bringing Pacific

warmth to the North Atlantic.

The ocean conveyor belt has run more or less smoothly since the

end of the last Ice Age. But global warming may now throw a spanner

into its workings. The planet is undoubtedly warming up, even if

people still argue about how much of this is due to human activities,

and the extra heat is melting ice in the Arctic Ocean. The ice turns

into fresh water, which flows into the salty North Atlantic.

The danger is that this fresh water might dilute the salty current

of the Gulf Stream so much that it stops sinking down into the ocean

depths near Iceland. If the Gulf Stream does stop, there will be

nothing pushing the deep cold river at the bottom of the North Atlantic.

As the Atlantic portion of the ocean conveyor belt grinds to a halt,

then Europe could indeed freeze ‚ ironically, as a direct result

of global warming.

Global Warming Kicks In

If that weren't enough, the ocean current specialists have just

found something else to worry about. Global warming may interfere

with not just the North Atlantic currents, but may disrupt the entire

system of ocean currents ‚ affecting the entire world's weather.

Leading the new investigation is Wallace Broecker and his colleagues

at Columbia University, New York. They start with evidence that

the great ocean currents tend to make the climate in the Earth's

two hemispheres change in opposite directions: when the north is

hot, the south is colder ‚ and vice versa. In Europe, most

of the past millennium (from about 1300 to 1800) was so cold that

it has been dubbed 'The Little Ice Age'. Some researchers have blamed

the Little Ice Age on a slowdown in the ocean current system that

includes the Gulf Stream. But Broecker takes the analysis a stage

further. At the same time, he says, the southern currents were stronger,

and - in a mirror image of the Little Ice Age - the Antarctic region

warmed up, perhaps by as much as 3 oC.

The link involves the ocean rivers that flow along the coast of

Antarctica ‚ the deep cold currents flowing back from the South

Atlantic, south of Africa and Australia. Cold, salty water off the

Antarctic coast sinks down into the depths, adding its push to the

interlinked system of ocean currents.

|

The perpetual chill of Antarctica helps to drive the ocean conveyor

belt, as cold salty water sinks to join the deep current flowing

from the Atlantic to the Pacific. But latest measurements show

a slow-down in the sinking Antarctic waters. |

|

|

photo

- Sean Leslie

|

|

In his latest research, Broecker and his colleagues at Columbia University,

New York, have just announced that the surface water near Antarctica

is sinking at only a third of the rate it was a century ago.

This has really set the cat among the climatological pigeons.

If Broecker is right, the slowdown in the Antarctic deep current

‚ starting about a century ago ‚ ought to be doing two

things. It should make the Antarctic colder, and also encourage

the Gulf Stream to make Europe warmer.

The latter result can explain one baffling aspect of global warming.

Temperature records - mainly from the northern hemisphere ‚

show that the present phase of global warming actually began in

the 1880s, before the man-made greenhouse effect got going. It accelerated

in the 1970s, when greenhouse gases started to fill the atmosphere.

So what we are seeing now ‚ in the northern hemisphere, anyway

- could be a combination of the recent man-made greenhouse effect

with a longer-term natural warming trend, powered by changes in

the ocean currents.

In Europe, that would mean the climate getting hotter more quickly

than the forecasters have predicted. But in the region around Antarctica,

the situation is by no means as clear-cut. Here, Broecker's analysis

means that man-made warming is fighting against a natural cooling

trend - and nobody knows what the consequences of that might be.

But one thing is for certain. As we enter the 21st century, the

links between ocean currents and weather are moving from academic

analysis into a matter of life and death around the globe.

Copyright © FirstScience.com

Dr John Gribbin is a best-selling author of popular

books on science, ranging from climatology to cosmology and quantum

physics. Formerly a researcher at Cambridge, he is now Visiting Fellow

in Astronomy at the University of Sussex. Gribbin is Physics Consultant

to New Scientist magazine. His books include In Search of

Schrodinger's Cat, The Hole in the Sky, Stephen Hawking: A Life in

Science (with Michael White), and The Little Book of Science