|

Astronaut and explorer Jim Reilly tells what

it's like to do construction work in the far-out environment of

space.

by Karen Miller

Jim Reilly, astronaut: "One of my favourite

memories is hanging out with just one hand on the space station, and

then swinging out so I could look across the Earth. The atmosphere

is really transparent, so you can see a lot of detail on the surface

below. One time when I had a chance to hang out on the bottom of the

station, the

sunset was coming. I left my lights off so I could watch the Sun

go down. And as it went down, the stars started popping out. Of course

they don't twinkle. They're all different sizes, and even different

colours, in space... At night you can see lightning flashes from thunderstorms

on the surface down below. You can get this blue light flashing, and

in this case I was able to see it flashing off the bottom of the station.

And as I was watching all this, we flew through the edges of the aurora,

kind of green and white curtains as we flew past."

"It was pretty spectacular," he added with a degree

of understatement.

Space walking astronauts like Reilly can't afford

to be star-struck, though. They do a dangerous job that requires

concentration. Floating two hundred miles overhead where a careless

motion could send them spinning into the void, modern-day astronauts

connect power lines, deploy antennas, haul supplies. They service

satellites and bolt modules to the space station. They're construction

workers, points out NASA engineer Phil West.

On Earth, most construction workers need little

more than a hardhat for protection. They can move their arms anywhere

they want. And if they drop something, it doesn't drift away.

In space, all that changes.

The thing that Jim Reilly was always most conscious

of, he recalls, was the need to slow down his motions. The astronauts

train in water, explains Reilly, who's flown two missions, and who

last summer installed an airlock on the International Space Station

(ISS). That training accustoms them to weightlessness. But water

is not the same as space. Unlike vacuum, water is dense; it pushes

back. "The water helps dampen your movements,” says Reilly.

"You can do things that if you did them in outer space, you would

go out of control."

more

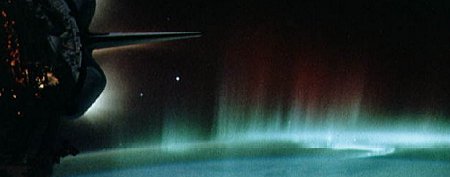

Orbiting

hundreds of kilometers above Earth, the space shuttle sometimes

glides right through spectacular auroras. Astronauts on

board Space Shuttle Discovery captured this image in 1991.

|

If you turn a bolt, for example, you

must remember there is no water to hold you in place, and that you

can push yourself off pretty fast if you don't pay attention. "You

learn," he says, "to bring yourself to a stop, and then make yourself

motionless, without any momentum remaining. Then, you can do whatever

needs to be done." You always have to think, he says, do I need

to do this task a little slower?

But it's not only weightlessness that

the astronauts deal with. The space suit itself forces astronauts

to adjust some deeply ingrained habits. The suit is pressurized

to 4.3 psi (pounds per square inch). That's less than one-third

of the pressure of Earth's atmosphere at sea-level (14.7 psi). The

air pressure outside a airplane flying at 35,000 feet is near 4.3

psi. It's also about the same as the extra pressure that keeps a

football inflated, says Reilly. And, like a football, the suit is

hard to bend.

The inflated

arms and bulky gloves of a space suit render some motions

- like reaching to the side and grabbing small objects -

unfamiliar and difficult.

|

To make it easier for astronauts to

move, the suit's engineers designed in joints: elbows, shoulders,

knees. But those joints can offer only a limited range of motion.

That means, Reilly explains, that in

space you can only work in the approximately three foot by three

foot by one foot area directly in front of you. It takes some getting

used to. "When you start your training, you have to start thinking

about the different ways you need to manoeuvre to get to the different

positions," says Reilly. "There are certain moves that you don't

want to try, because you'll be working against the suit."

For example, let's say that you wanted

to grab an object off to the side. You wouldn't just reach out for

it, like you would on Earth. The shoulder joint rotates front to

back - not side to side. You could move your arm sideways by bending

the inflated arm of the suit. That's not impossible, notes Reilly,

but it does take some effort. It's easier to rotate your body until

you're facing the object and then reach it by moving your arm forward.

The gloves, Reilly says, are one place

where the pressure is especially noticeable. They're designed so

that there's little strain when your hand is at rest, but as a result,

when you open your hand, you push against the resistance of the

glove. To understand the effort involved, Reilly suggests this exercise:

Close your hand, put a rubber band around your fingers, and then

open your hand fifteen times as far as it will go. The strain on

the muscles in your forearm, he says, is exactly the same as in

space.

Astronaut

Jim Reilly, mission specialist, is pictured at the Johnson

Space Center in February 2001

|

There's more, of course. You can't whistle

in a spacesuit, because the air pressure's too low. Tools must be

two to three times larger than normal because the gloves are so bulky.

You hear the constant loud whine of the fan that circulates the atmosphere

within the suit. But you adapt. The suit became very comfortable,

says Reilly, and wearing it began to feel like second nature to him.

"As we were getting ready for our first EVA, Yury

Usachev, who was commander of Expedition Two [on the ISS], came

by. We were chatting about suit use, and things to watch out for.

He just wanted to make sure that we were aware that it's very very

dangerous outside. And it is. We were always conscious of that.

But he said one thing at the end: 'In spite of all that, when you're

working, just make sure you take a couple of seconds to just look

up every once in a while, and look around.'

"That was the best piece of advice he gave me,"

says Reilly. "Because every once in a while, just for 10 seconds,

I'd stop and look around, and see what part of the planet I was

over, and look at the horizon . . .it was really a joy to do that

work. I hope I get a chance to do it again"

|