|

By Patrick

L. Barry

Scientists are

using two orbiting research satellites to peer into the centre of

storms in ways that were never before possible, in a bid to understand

what happens at the heart of a hurricane. Unlike most weather satellites

that can only take pictures of a hurricane's cloud tops, NASA's QuikScat

and Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission (TRMM) satellites carry

microwave sensors that can "see" through the clouds and scrutinise

conditions -- including rainfall, wind and water temperature -- at

the ocean's surface. This data could allow researchers to detect tropical

depressions earlier and to predict where hurricanes are headed with

greater accuracy.

"I think the

rain and the wind together is a very powerful tool to study hurricanes,"

said Dr. Timothy Liu, project scientist for the QuikScat mission

at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

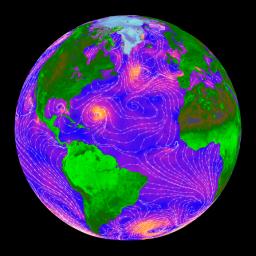

QuikScat, which

was launched in June 1999, uses an instrument called a "radar scatterometer"

to measure both the speed and the direction of surface winds over

the world's oceans.

Other radar-based

satellites can measure wind speed, Liu said, but "the only thing

that can measure the wind vector -- that is, the speed and the direction

together -- is the scatterometer."

A scatterometer

works by sending a beam of microwave radiation toward the ocean

surface at an angle. The beam, which passes undisturbed through

clouds, gets scattered by the ocean surface, and some of the microwaves

bounce back toward the satellite. A rougher ocean surface,

which indicates higher winds, will reflect more radiation back toward

the satellite than a smooth surface will.

Liu and Dr.

Kristina Katsaros of NOAA found that the wind data from QuikScat

could be used to identify potential hurricanes one to three days

before traditional methods.

Part of the

reason for this, Liu said, is that the satellite photographs used

by the National Hurricane Centre show only the cloud tops of forming

hurricanes, which sometimes can be obscured from view by higher

clouds.

Another key

to understanding and predicting hurricanes is rainfall. Rainfall

snapshots are produced by the TRMM (Tropical Rainfall Measuring

Mission) satellite, which is a joint mission between NASA and the

National Space Development Agency (NASDA) of Japan.

Courtesy JPL

A

snapshot of the speed and direction of ocean surface winds

taken by QuikScat. Pink and yellow represent high velocity

winds, and purple and blue represent slower winds. The

white lines and arrows indicate direction.

|

"The big impact

that the rainfall data can have is that the rainfall in these tropical

storms are signatures of the amount of latent heat that's being

released into the atmosphere," said Dr. Marshall Shepherd, a research

meteorologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre

Incorporating

rainfall data from TRMM into computer weather models "gives the

model a better handle on the energetics that are required to drive

the circulation, to drive the hurricane and also affect its path,"

Shepherd said.

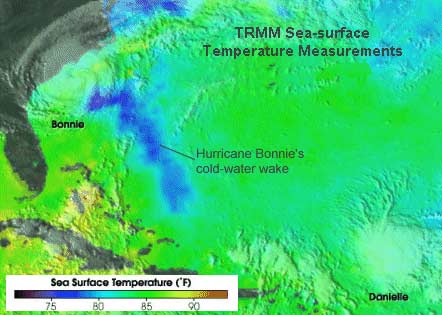

The TRMM satellite

can also use its microwave sensors to measure ocean surface temperatures

beneath a hurricane.

"Hurricanes

are intimately tied to the sea surface temperature," Shepherd said. "There's

generally kind of a threshold temperature (above which) hurricanes

like to form. If you have all of the other a priori

conditions in place, and if you have ample warm sea surface temperature

and moisture, then you can get a hurricane that likes to grow,"

Shepherd said.

Higher sea surface

temperatures mean more evaporation of ocean water into the air. As

that moisture condenses into clouds, it releases heat to the air

that causes the air to rise. The rising air creates a low pressure

area beneath it that pulls the surrounding air spiralling inward,

perpetuating the hurricane.

"It's that conversion

of latent heating that's carried from the water vapour when it condenses

to form the clouds in the hurricane -- that's really the fuel supply

that powers the hurricane engine,'" Shepherd said. "We tend

to think of hurricanes as big heat engines."

Low sea surface

temperatures can spell death for a hurricane, as in 1998 when the

"wake" of cold water behind Hurricane Bonnie caused Hurricane Danielle,

which was following close behind, to dissipate.

(TMI)

sea-surface temperatures - Blues represent cooler water, greens

and yellows are warmer water. TMI is the first satellite microwave

sensor capable of accurately measuring sea surface temperature

through clouds.

|

Traditional

weather satellites that use infrared sensors can also measure sea

surface temperature, but "the big advantage that the TRMM microwave

imager has ... is that microwave instruments can see through clouds,

whereas infrared instruments (on traditional weather satellites)

can only give you sea surface temperatures in clear regions," Shepherd

said.

While the kind

of rainfall and sea surface temperature data produced by TRMM holds

great potential for improving hurricane forecasting, TRMM is not

primarily a hurricane-monitoring satellite.

"Things like hurricane monitoring ... are extra benefits of the satellite,

but its main mission is to measure rainfall," Shepherd said. "TRMM

is a research mission -- it wasn't designed to be used in an operational

setting.

"But where the

data can be used, I'm sure it is ...."

|