|

When humans go to the moon or Mars, they'll

probably take plants with them. NASA-supported researchers are learning

how greenhouses work on other planets.

by Karen Miller

Confused? Then you're

just like plants in a greenhouse on Mars.

No greenhouses exist

there yet, of course. But long-term explorers, on Mars, or the moon,

will need to grow plants: for food, for recycling, for replenishing

the air. And plants aren't going to understand that off-earth environment

at all. It's not what they evolved for, and it's not what they're

expecting.

But in some ways, it

turns out, they're probably going to like it better! Some parts

of it, anyway.

"When you get

to the idea of growing plants on the moon, or on Mars," explains

molecular biologist Rob Ferl, director of Space Agriculture Biotechnology

Research and Education at the University of Florida, "then

you have to consider the idea of growing plants in as reduced an

atmospheric pressure as possible."

There are two reasons.

First, it'll help reduce the weight of the supplies that need to

be lifted off the earth. Even air has mass.

Second, Martian and

lunar greenhouses must hold up in places where the atmospheric pressures

are, at best, less than one percent of Earth-normal. Those greenhouses

will be easier to construct and operate if their interior pressure

is also very low - perhaps only one-sixteenth of Earth normal.

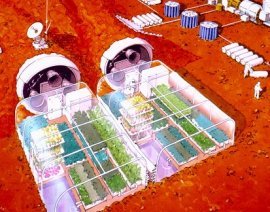

An

artist's concept of

Greenhouses on Mars.

|

The problem is, in

such extreme low pressures, plants have to work hard to survive.

"Remember, plants have no evolutionary preadaption to hypobaria,"

says Ferl. There's no reason for them to have learned to interpret

the biochemical signals induced by low pressure. And, in fact, they

don't. They misinterpret them.

Low pressure makes

plants act as if they're drying out.

In recent experiments,

Ferl's group exposed young growing plants to pressures of one-tenth

Earth normal for about twenty-four hours. In such a low-pressure

environment, water is pulled out through the leaves very quickly,

and so extra water is needed to replenish it.

But, says Ferl, the

plants were given all the water they needed. Even the relative humidity

was kept at nearly 100 percent. Nevertheless, the plants' genes

that sensed drought were still being activated. Apparently, says

Ferl, the plants interpreted the accelerated water movement as drought

stress, even though there was no drought at all.

That's bad. Plants

are wasting their resources if they expend them trying to deal with

a problem that isn't even there. For example, they might close up

their stomata - the tiny holes in their leaves from which water

escapes. Or they might drop their leaves altogether. But, those

responses aren't necessarily appropriate.

An

experiment related to Ferl's: Lettuce growing in a low-pressure

dome at the Kennedy Space Center.

|

Fortunately, once the

plants' responses are understood, researchers can adjust them. "We

can make biochemical alterations that change the level of hormones,"

says Ferl. "We can increase or decrease them to affect the

plants' response to its environment."

And, intriguingly,

studies have found benefits to a low pressure environment. The mechanism

is essentially the same as the one that causes the problems, explains

Ferl. In low pressure, not only water, but also plant hormones are

flushed from the plant more quickly. So a hormone, for example,

that causes plants to die of old age might move through the organism

before it takes effect.

Astronauts aren't the

only ones who will benefit from this research. By controlling air

pressure, in, say, an Earth greenhouse or a storage bin, it may

be possible to influence certain plant behaviours. For example,

if you store fruit at low pressure, it lasts much longer. That's

because of the swift elimination of the hormone ethylene, which

causes fruit to ripen, and then rot. Farm produce trucked from one

coast to the other in low pressure containers might arrive at supermarkets

as fresh as if it had been picked that day.

Much work remains to

be done. Ferl's team looked at the way plants react to a short period

of low pressure. Still to be determined is how plants react to spending

longer amounts of time - like their entire life - in hypobaric

conditions. Ferl also hopes to examine plants at a wider variety

of pressures. There are whole suites of genes that are activated

at different pressures, he says, and this suggests a surprisingly

complex response to low pressure environments.

Peas

growing onboard the International Space Station. Ferl's

research will improve greenhouses not only on other planets,

but also on spaceships

|

To learn more about

this genetic response, Ferl's group is bioengineering plants whose

genes glow green when activated. In addition they are using DNA

microchip technology to examine as many as twenty-thousand genes

at a time in plants exposed to low pressures.

Plants will play an

extraordinarily important role in allowing humans to explore destinations

like Mars and the moon. They will provide food, oxygen and even

good cheer to astronauts far from home. To make the best use of

plants off-Earth, "we have to understand the limits for growing

them at low pressure," says Ferl. "And then we have to

understand why those limits exist."

Ferl's group is making

progress. "The exciting part of this is, we're beginning to

understand what it will take to really use plants in our life support

systems." When the time comes to visit Mars, plants in the

greenhouse might not be so confused after all.

|