|

The early technology trail blazed boldly and

brightly, and in the space of a only a few years we have now begun

to look back at computer history in a quest to make sense of where

we might be going.

By Dr Christine Finn

Humans, of course have a memory strongly

connected with smells, and as soon as I walked into the computer museum,

the smell hit me in the head, and I remembered the old days in which

I spent a lot of time around these old "computing engines".

Stan

Mazor, Intel pioneer, November 2000.

Like a laptop next to an ENIAC, the Computer Museum History Centre

is dwarfed by the giant hangar of the historic NASA Ames base at Moffett

Field in Mountain View. But not for long. A major scheme over the

next few years will convert Hangar 1 into NASA's California Air and

Space Centre and a much-enlarged History Centre will be right next

door. It's designed to be a world-class institution. It also develops

the idea of computer history as a resource, and one which is set smack

in the heart of Silicon Valley, putting it within its own geographical

context. The visitor will reach the Centre by driving through the

technological hub, and emerge back into it. Here, for the most part,

past and present will collide.

The comprehensive tech collection at Boston's

Science Museum performs the same function on the east coast, drawing

its context from the innovations of Route 128. Apart from such science

museums, for which computers are part of a broader history, those

institutions dedicated to new technology have a display which features

a familiar array stretching back over the past century and a half.

Some have examples of the forerunners to computers, the era which

claims Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace. A few Heath Robinson-type

machines make an appearance. An example of an early Cray - the world's

first supercomputer - is a popular as well as a

Courtesy Ashfield District Council

Early Portrait

of Ada Lovelace

|

well-known name. It is also an example of function and design in combo,

the circular seat shape being the most efficient way of wiring the

machine.

The Computer

Museum History Centre is a non-profit body founded in 1996. Its

mission is to preserve and present for posterity the artefacts and

stories of the information age. At November 2000, its holdings included

more than 3,000 artefacts, 2,000 films and videotapes, 5,000 photographs

and 2,000 linear feet of catalogued documentation and gigabytes of

software. Documentation ranges from advertisements to programming

manuals.

The Museum acknowledges itself to play a unique role in the history

of the computing revolution and its worldwide impact on the human

experience. The role of individuals in this process is crucial, as

those who owned, or even played a role in the design of, early machines

donate much of the material. As at Intel Corporation's in-house museum,

the artefacts can generally be traced back to a source, and through

that process the stories, retold. Technical lectures and talks are

a vital part of the Museum's work.

Courtesy Intel Corporation

Artifacts,

Intel Museum, Santa Clara

|

John Toole, the Museum's CEO, tells me that for the retired tech worker,

the chance of describing his role in the development of the early

technology can be emotionally cathartic. One man was moved to tears,

and explained that this was the first opportunity he'd had to tell

his story.

It receives a range of donations - from hardware and software, to

audio recordings and ephemera - and given the quantities of machines

produced, particularly personal computers, the potential material

base is enormous.

The Centre also specifies what it doesn't want. It's difficult for

us to turn people away when they have taken the time to contact us

about a particular item. Sadly, we must do this when the item in question

is something the History Centre already has or has decided does not

meet the Collections criteria.

As at November 2000, some of the items no longer accepted included

the following: IBM PC, IBM PC Jr, Commodore PET, Commodore 64, Commodore

VIC-20, Apple II (+/c/e) TI 99/4, Times Sinclair. These items were

made in large quantities and they have enough representative samples

of them already. The Centre supports the recycling of unwanted machines.

The smaller-scale Computer

Museum of America, on the campus of Coleman College in La Mesa,

California, accepts all donations of computer-related materials except

for defective monitors. Working computers not used by the museum are

refurbished and donated to schools ands other non-profit organisations.

The CMA also has archive and research materials, and established a

Hall of Fame to honour those making major achievements in the computer

history field.

Image Courtesy Hewlett-Packard Company

Hewlett Packard

Garage, 367 Addison Avenue, Palo Alto

|

As computer history interest grows, individuals

and organisations are setting up other collections in different locations.

In America, as more tech hubs emerge outside the East and west coast

corridors, it suggests that before too long, it will be possible to

visit a range - however limited - of computer history at any drivable

distance. On the Internet, the Vintage Computer Festival and Classic

Computing sites flag up numerous user-groups with an interest in preserving

specific machines and associated material.

The Computer Museum History Centre

is part of a Silicon Valley tech-trail, which stretches from the corporation

museums, such as Intel, to the significant Tech Museum of Innovation

affectionately known as the Tech - in San Jose. The trail includes

the headquarters of household names and the space-time relationship,

which is their evolution across Silicon Valley. In San Jose, the expanding

Cisco buildings are little short of a form of monumental corporate

architecture in style and scale. The development of a company's research

headquarters as a campus has spawned significant landmarks, such as

the Sun campus, which incorporates historical motifs in a mission-style

in keeping with the area's architectural heritage.

Low-key in scale but highly significant historically are the founding

locations of the significant companies. These include the garages

associated with the early days of Apple and Hewlett Packard. In these

buildings the first key developments were made. In Palo Alto, the

company bought the Hewlett Package garage, with house attached, in

late 2000 - for more than $1 million.

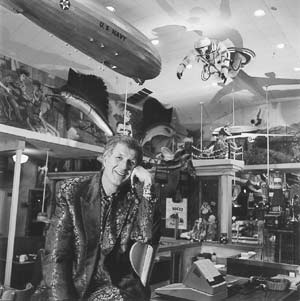

Image Courtesy Michael Steinberg

Jamis MacNiven

at Bucks Diner, Woodside

|

Another historical location is Bucks. A cultural icon that thinks

it's an American diner. It's a place which marks time in two ways.

The historic high-tech deals done over breakfast, and the assemblage

of things hanging from, attached to, gracing and playfully disgracing

its walls. A pretend Russian cosmonaut dangles from the ceiling. A

sign from a nuclear fall-out shelter is close by displays of pens,

thermometers, silicon chips and wafers, ribbons and braids, swords,

a flying fish, a broken John McEnroe tennis racquet. And that's just

for starters. Follow that visual smorgasbord with titbits of fascinating

conversation involving venture capitalists and tech entrepreneurs.

As it is, the owner Jamis MacNiven, who runs Bucks with his wife,

regards it as a museum of Jurassic Technology. Its diners number the

great and the good of Silicon Valley, who take breakfast early and

conclude their multi-million dollar deals over coffee and muffins.

Netscape was founded here, Yahoo! Was turned down twice. The Bucks

menu is a newsletter, the web page a gallery of fun and fame. James

used to be an artist in New York City. When I moved in here, it was

a white box, he says, casting around the walls. Now he maintains his

creativity by dreaming up ideas for the walls, and writing a film-script

about Silicon Valley.

If these walls could speak, this would be an oral history book of

Silicon Valley…

|