|

Finding

life on other planets (Aliens!) is a tantalising prospect that occupies

our daydreams. And yet with the constant onslaught of new technology

are we fast approaching a time when it could become a reality?

By Bruce Dorminey

To humans, the idea of being alone in

a Universe at least 10 to 13 billion light years across is disconcerting.

The philosophical ramifications of being alone in such an overwhelming

expanse of spacetime cannot be overstated. Given everything we know

about the current rate of star and planetary formation, however, it

would seem illogical that we should be the only sentient beings in

the Universe. And given what we do know about the structure of life

here on Earth and of molecules found thus far in the interstellar

medium, it would appear that carbon could be the key to life's development

anywhere in the Universe.

While we can only continue to speculate

about the extraterrestrial development of life and intelligence,

we do know that carbon production is based on the rate of star formation.

Estimates by the Hubble Space Telescope strongly suggest that carbon

production peaked almost 7 billion years ago. Given the time span

necessary for biological evolution as we know it, some theorists

now believe that it is highly unlikely that the Universe could have

seen the first carbon-based intelligent life any sooner than 3 billion

years ago, or when the Universe was already more than 10 billion

years old. In other words, the evolution of extraterrestrial intelligent

life could be a very "recent" cosmic phenomenon. In fact,

as Mario Livio from the Space Telescope Science Institute and Charles

Lineweaver from the University of New South Wales in Sydney have

both pointed out, the Universe may only just be awakening to an

epoch of intelligent life. As Lineweaver has noted, at this stage

in our own development, it is impossible to know whether we have

come late or early to the cosmic party, but in the long history

of our Universe, we might be relative newcomers.

What kind of

transport and communications can we expect ET to have?

|

If there are extraterrestrial civilizations

capable of communicating as we do, shouldn't it follow that the

same basic physics also held for their evolution? Life as we know

it, has its best chance of developing on an Earth-like, fast-rotating

planet in orbit around a Sun-like star, which has a hydrogen-burning

phase that would provide a stable environment for life to evolve.

And even with those parameters in place, ETs would likely emerge

only after their home world had developed some sort of genetic code.

They would also have to become cognizant enough to communicate with

each other. Yet in order to communicate over interstellar distances,

extraterrestrials would first have to overcome the gravity of their

own planet. In order to communicate with us, as Seth Shostak of

the SETI Institute frequently points out, they would have to develop

the dexterity to build technology and telescopes.

If they chose radio, they could easily

overcome the universal cacophony of background noise in the electromagnetic

microwave region (1,000 to 100,000 megahertz). Just above the terrestrial

TV and FM bands, it is relatively quiet. There, only a trace of

background radiation from the Big Bang remains. (This is an effect

anyone can hear in the form of soft constant static when flipping

the dials on an FM radio.) However, the pursuit of ET in the radio

spectrum has a short history. Although decades, even centuries earlier,

there were many ideas about how to signal or find extraterrestrial

civilizations, the genesis of modern SETI really began only some

40 years ago.

In a paper published in Nature in 1959,

the Cornell University physicists Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison

suggested that the most effective way of communicating across galactic

distances had to be via radio waves. At about the same time, Frank

Drake, a young radio astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy

Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia, was working on a pet project

named Ozma. (The name came from the mythical Princess Ozma, featured

in L. Frank Baum's fabled Land of Oz: a place far, far away, populated

with strange and exotic beings.)

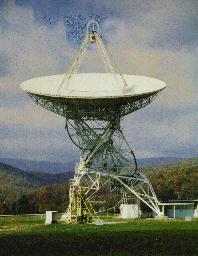

NRAO and Associated Universities Inc.

The 26 metre

(85 foot) Tatel

Radio Telescope which was built in 1958.

|

Drake became the first radio astronomer

to attempt to detect interstellar radio transmissions from an extraterrestrial

intelligence. On April 8, 1960, he used the novel combination of

sensitive new receivers and a 26-metre radio telescope to survey

several nearby stars, the first of which was Tau Ceti, an early-morning

star in the Cetus constellation some 3.3 parsecs (a parsec being

a distance of approximately 3.26 light years) from Earth. Drake

picked up a strong signal almost as soon as he began scanning with

his single, 100-hertz receiver at the 21-centimetre emission line

(1,420 megahertz), which is the emission frequency of cold hydrogen

from interstellar space. Yet some weeks later, Drake learned that

the "signal" was really terrestrial interference from

a secret U.S. military project.

Despite this frustrating experience

with radio frequency interference (RFI), Drake's efforts prompted

a request from the National Academy of Sciences asking that he organize

a 1961 meeting to discuss the budding Search for Extraterrestrial

Intelligence, or SETI and shortly thereafter the institute was founded.

As University of Arizona astronomer

Neville Woolf points out, looking for evidence of ETI in the radio

spectrum could well be futile, because the ETI may have long moved

on to more advanced forms of communication, which our own technologically

primitive civilization has yet to realize. "Radio SETI is a

noble search", says Woolf. "Yet, if we were to look for

ETI technologies by looking for giant steam engines, people would

laugh because they would say that's old technology. But what's old

on the scale of a Universe that's 10 billion years old?

Ly Ly/SETI

Institute

An Artist's

Conception of the Allen Telescope Array, due to go into full

operation by 2005 in the California Sierra mountains northeast

of San Francisco. With its eventual collection of more than

1,000 antenna, its SETI target list will ultimately number

as many as a million stars.

|

In truth, no matter how dogged our

efforts to find extraterrestrial intelligence, and how advanced

the technologies, SETI astronomers may still miss the mark. "Back-of-the-envelope"

calculations on the median age of possible extraterrestrial civilizations

suggest their technologies would be several million years ahead

of ours. Thus, trying to detect their communications or signals

in the radio and optical spectrums may indeed be as futile as trying

to log on to the Internet by banging on a "talking" drum.

How can we second-guess an extraterrestrial civilization that could

be millions of years ahead of us, if we cannot accurately envisage

what Earth technology will bring in only several hundred years?

We've moved from basic laptop computers to wireless Dick Tracy-style

communicating watches in 10 years. What will be wrought in 10 million

years? As Stuart Bowyer, a retired Berkeley radio astronomer and

long-time SETI advocate, reminded me, we are simply stuck with the

physics that we understand thus far. Bowyer believes that even if

other civilizations are very advanced, communication in both the

radio and optical spectrums will remain viable, and, therefore,

should remain central to SETI's overall approach. He asserts that

in the next 40 years, or by the time NASA and ESA have produced

high-resolution images of an extra-solar "earth", SETI

astronomers will have had a "fair chance" of finding extraterrestrial

technology.

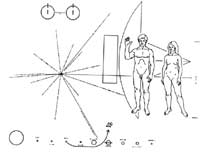

The Pioneer

F spacecraft, destined to be the first man made object to

escape from the solar system into interstellar space, carries

this pictorial plaque. It is designed to show scientifically

educated inhabitants of some other star system, who might

intercept it millions of years from now, when Pioneer was

launched, from where, and by what kind of beings. (With the

hope that they would not invade Earth!)

|

But even if a signal, or "leakage",

is detected, it would be doubtful that we could decipher it, unless

it was intended as an all-points-directed beacon designed to be

decipherable for any civilization that lay in its beam. Certainly,

signal detection would confirm that we were not alone in the Universe,

but true interstellar communication, even over short distances,

would necessitate a transgenerational attitude of collective long-term

effort. Signals sent and returned over distances as short as 10

parsecs would require a round-trip communication transit of at least

65 years, or basically a human lifetime. Sustaining such interest

in the public at large may prove to be optimistic at best. Imagine

a student in a third-grade class some time in the future: the teacher

announces that SETI astronomers have just detected a signal containing

a message from an intelligent technology-bearing extraterrestrial

civilization on an Earth-like planet circling a nearby star. The

announcement would initially be greeted with emotions ranging from

excitement, consternation, curiosity, and bewilderment. Universities

would likely offer whole new curricula based on how Earth's religions

and philosophies would be affected by the news. The Nobel Committee

would award prizes, and the media would have a field day. But by

the time the message had been deciphered, and the international

community had agreed upon and sent humanity's response, the student

would hear the news of ET's reply as he was "getting the gold

watch" at his retirement party. So, dreams of interstellar

E-mail are slightly optimistic.

While profound certainly, the detection

of an alien intelligence, even within 100 parsecs from Earth, would

not be something that most people would think about on a day-to-day

basis. Life would simply go on.

|

An Abridged extract from 'Distant Wanderers' by Bruce Dorminey

(C) By permission of (Copernicus

Books,$29.95/£22) An imprint of Springer-Verlag

New York, Inc

Available to buy from Amazon.co.uk

and Amazon.com.

Bruce Dorminey was a winner

in the Royal Aeronautical Society's Aerospace 1998 Journalist

of the Year Awards. He writes about astronomy and astrophysics

for numerous publications. This is his first book.

|

|

|

|