|

On the ground, the International Space Station would be an odd

looking building - but space is an odd place to live!

by

Patrick L.Barry

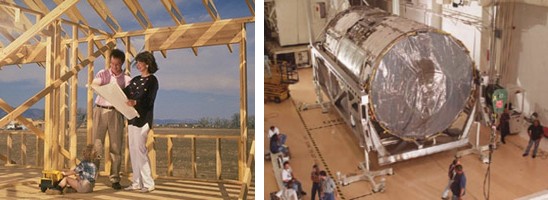

Homes on Earth

provide shelter from the wind and rain. But a home in Earth orbit

must shield its occupants from the solar wind, and it must

withstand a steady rain of dust-sized meteoroids, many moving faster

than a speeding bullet!

A terrestrial

house has insulation

to keep the air inside cool or warm, but a space home must be tightly

sealed just to keep the air inside.

The structure

of earthbound buildings must support a constant gravitational pull

of 1-g. In contrast, an orbiting structure's design should make

sense in microgravity, and at the same time be able to withstand

the tremendous 3-g acceleration of a rocket blasting into space.

For these and

other reasons, building a structure for living in space poses a

different set of design challenges than building homes on the ground.

The first thing

an architect would notice about building in space is the pull of gravity

-- or rather the lack thereof! A freely-falling space home in Earth

orbit can take a wider variety of basic shapes than homes on the planet

below.

"It's in free

fall, so there's no need to say 'this is up' and 'this is down'

from the standpoint of the station's architecture and structural

integrity," said Kornel Nagy, structural and mechanical systems

manager for the International Space Station (ISS) at NASA's Johnson

Space Centre.

For example,

science fiction writers often imagine that a space station would

be wheel shaped. As seen in the Stanley Kubrick / Arthur C. Clarke

science fiction classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, these ring-shaped

outposts would slowly rotate to create a centrifugal pull that acted

as a false gravity. Other visionaries, such as NASA's own Wernher

von Braun (see our article, Wheels

in the Sky), also saw a spinning wheel as the most likely space

station design.

So why does

the ISS look more like an Erector Set than a big hamster wheel?

"Even though

(the wheel design is) an elegant concept," says Nagy, "you have

to think in terms of the current launch vehicles that we have and

how you get all the pieces on board and assembled into a unified

body."

"So the option

that was looked at is to take the pressurised compartments up in

segments that are as big as you can lift in a particular launch

vehicle," he continued. "In our case, it's the Shuttle payload bay."

NASA

Building

a home for living in space requires a little more than plywood

and two-by-fours. Titanium, Kevlar, and high-grade steel are

common materials in the ISS. Engineers had to use these materials

to make the structure lightweight yet strong and puncture-resistant.

|

Because each

of the aluminum-can shaped components of the Station has to be lifted

into orbit, minimising weight is crucial. Lightweight aluminium,

(rather than constructing a steel

building), comprises most of the outer shell for the modules.

This shell must

also provide protection from impacts by tiny meteoroids and man-made

debris. Because the ISS zips through space at about 27,000 km/h,

even dust-sized grains present a considerable danger. Man-made debris,

a drifting legacy of past space exploration, poses an even greater

threat.

To ensure the

safety of the crew, the Space Station wears a "bullet-proof vest."

Layers of Kevlar, ceramic fabrics, and other advanced materials

form a blanket up to 10 cm thick around each module's aluminium

shell. (Kevlar is the material used in the bullet-proof vests used

by police officers.)

"This protective

shielding was tested by shooting at it with high-velocity guns to

verify that it is indeed a good protection material," Nagy said.

NASA

Layers

of Kevlar and other impact-resistant materials reduce the

chance that small debris could penetrate the modules' walls

and endanger the crew.

|

Designers had

to leave a few holes in this armor so the crew could occasionally

enjoy the spectacular view.

A typical window

for a house on Earth has 2 panes of glass, each about 1/16 inch

thick. In contrast, the ISS windows each have 4 panes of glass ranging

from 1/2 to 1-1/4 inches thick. An exterior aluminium shutter provides

extra protection when the windows are not in use.

The glass in

these windows is subject to strict quality control, because even

minute flaws would increase the chance that a micro-meteoroid could

cause a fracture.

In orbit, a

major force is the pressure of the air inside the ISS, which presses

on each square inch of the modules' interior with almost 15 pounds

of force. (Homes on Earth also have this internal pressure, but

the external pressure of the atmosphere balances it out.)

But even before

reaching orbit these modules must also hold up to the massive stresses

of launch.

"The structure

has to withstand the loading it will see while being transported

to orbit, which is a pretty intense environment," Nagy said.

As the Shuttle

climbs toward the edge of space, every piece of the ISS module inside

will "weigh" three times normal. The structure of the modules must

handle both this loading along the long axis during launch and the

internal air pressure while in orbit.

Once the Shuttle

has carried a module into orbit, the task remains to securely attach

it to the rest of the Station.

The US-designed

Common Berthing Mechanism (or CBM) links together the modules. To

ensure a good seal, the CBM has an automatic latching mechanism

that pulls the two modules together and tightens 16 connecting bolts

with a force of 19,000 pounds each! This huge force is needed to

counteract the tendency of the internal air pressure to push the

modules apart and to ensure a good air-tight seal.

"A lot of development

work, a lot of testing, and a lot of certification went into the

CBM to be able to achieve that reliable seal," Nagy said. "So far

it's worked well."

|